Credits/Image: NASA, ESA, Alessandro Savino (UC Berkeley), Joseph DePasquale (STScI), Akira Fujii DSS2.

Credits/Visualization: NASA, ESA, Christian Nieves (STScI)

Science: Alessandro Savino (UC Berkeley)

Acknowledgment:Joseph DePasquale (STScI), Frank Summers (STScI), Robert Gendler

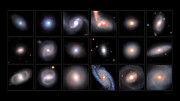

These satellite galaxies represent a rambunctious galactic "ecosystem" that NASA's Hubble Space Telescope is studying in unprecedented detail. This ambitious Hubble Treasury Program used observations from more than a whopping 1,000 Hubble orbits. Hubble's optical stability, clarity, and efficiency made this ambitious survey possible. This work included building a precise 3D mapping of all the dwarf galaxies buzzing around Andromeda and reconstructing how efficiently they formed new stars over the nearly 14 billion years of the universe's lifetime.

In the study published in The Astrophysical Journal, Hubble reveals a markedly different ecosystem from the smaller number of satellite galaxies that circle our Milky Way. This offers forensic clues as to how our Milky Way galaxy and Andromeda have evolved differently over billions of years. Our Milky Way has been relatively placid. But it looks like Andromeda has had a more dynamic history, which was probably affected by a major merger with another big galaxy a few billion years ago. This encounter, and the fact that Andromeda is as much as twice as massive as our Milky Way, could explain its plentiful and diverse dwarf galaxy population.

Surveying the Milky Way's entire satellite system in such a comprehensive way is very challenging because we are embedded inside our galaxy. Nor can it be accomplished for other large galaxies because they are too far away to study the small satellite galaxies in much detail. The nearest galaxy of comparable mass to the Milky Way beyond Andromeda is M81, at nearly 12 million light-years.

This bird's-eye view of Andromeda's satellite system allows us to decipher what drives the evolution of these small galaxies. "We see that the duration for which the satellites can continue forming new stars really depends on how massive they are and on how close they are to the Andromeda galaxy," said lead author Alessandro Savino of the University of California at Berkeley. "It is a clear indication of how small-galaxy growth is disturbed by the influence of a massive galaxy like Andromeda."

"Everything scattered in the Andromeda system is very asymmetric and perturbed. It does appear that something significant happened not too long ago," said principal investigator Daniel Weisz of the University of California at Berkeley. "There's always a tendency to use what we understand in our own galaxy to extrapolate more generally to the other galaxies in the universe. There's always been concerns about whether what we are learning in the Milky Way applies more broadly to other galaxies. Or is there more diversity among external galaxies? Do they have similar properties? Our work has shown that low-mass galaxies in other ecosystems have followed different evolutionary paths than what we know from the Milky Way satellite galaxies."

For example, half of the Andromeda satellite galaxies all seem to be confined to a plane, all orbiting in the same direction. "That's weird. It was actually a total surprise to find the satellites in that configuration and we still don't fully understand why they appear that way," said Weisz.

The brightest companion galaxy to Andromeda is Messier 32 (M32). This is a compact ellipsoidal galaxy that might just be the remnant core of a larger galaxy that collided with Andromeda a few billion years ago. After being gravitationally stripped of gas and some stars, it continued along its orbit. Galaxy M32 contains older stars, but there is evidence it had a flurry of star formation a few billion years ago. In addition to M32, there seems to be a unique population of dwarf galaxies in Andromeda not seen in the Milky Way. They formed most of their stars very early on, but then they didn't stop. They kept forming stars out of a reservoir of gas at a very low rate for a much longer time.

"Star formation really continued to much later times, which is not at all what you would expect for these dwarf galaxies," continued Savino. "This doesn't appear in computer simulations. No one knows what to make of that so far."

"We do find that there is a lot of diversity that needs to be explained in the Andromeda satellite system," added Weisz. "The way things come together matters a lot in understanding this galaxy's history."

Hubble is providing the first set of imaging where astronomers measure the motions of the dwarf galaxies. In another five years Hubble or NASA's James Webb Space Telescope will be able to get the second set of observations, allowing astronomers to do a dynamical reconstruction for all 36 of the dwarf galaxies, which will help astronomers to rewind the motions of the entire Andromeda ecosystem billions of years into the past.

The Hubble Space Telescope has been operating for over three decades and continues to make ground-breaking discoveries that shape our fundamental understanding of the universe. Hubble is a project of international cooperation between NASA and ESA (European Space Agency). NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, manages the telescope and mission operations. Lockheed Martin Space, based in Denver, also supports mission operations at Goddard. The Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, conducts Hubble science operations for NASA.

About This Release

Credits:

Media Contact:

Ray Villard

Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, Maryland

Science Contact:

Alessandro Savino

University of California, Berkeley, California

Permissions: Content Use Policy

Contact Us: Direct inquiries to the News Team.

Related Links and Documents

- Science Paper: The science paper by Alessandro Savino et al. (on ApJ), PDF (5.77 MB)

- NASA's Hubble Portal