NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle

Cambridge, MA -A new study provides new clues indicating that an exoplanet 500 light-years away is much like Earth.

Kepler-186f is the first identified Earth-sized planet outside the Solar System orbiting a star in the habitable zone. This means it's the proper distance from its host star for liquid water to pool on the surface.

The Georgia Tech study used simulations to analyze and identify the exoplanet's spin axis dynamics. Those dynamics determine how much a planet tilts on its axis and how that tilt angle evolves over time. Axial tilt contributes to seasons and climate because it affects how sunlight strikes the planet's surface.

The researchers suggest that Kepler-186f's axial tilt is very stable, much like the Earth, making it likely that it has regular seasons and a stable climate. The Georgia Tech team thinks the same is true for Kepler-62f, a super-Earth-sized planet orbiting around a star about 1,200 light-years away from us.

How important is axial tilt for climate? Large variability in axial tilt could be a key reason why Mars transformed from a watery landscape billions of years ago to today's barren desert.

"Mars is in the habitable zone in our solar system, but its axial tilt has been very unstable -- varying from 0 to 60 degrees," said Georgia Tech Assistant Professor Gongjie Li, who led the study together with graduate student Yutong Shan from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) in Cambridge, Mass. "That instability probably contributed to the decay of the Martian atmosphere and the evaporation of surface water."

As a comparison, Earth's axial tilt oscillates more mildly -- between 22.1 and 24.5 degrees, going from one extreme to the other every 10,000 or so years.

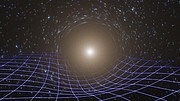

The orientation angle of a planet's orbit around its host star can be made to oscillate by gravitational interaction with other planets in the same system. If the orbit were to oscillate at the same speed as the precession of the planet's spin axis (akin to the circular motion exhibited by the rotation axis of a top or gyroscope), the spin axis would also wobble back and forth, sometimes dramatically.

Mars and Earth interact strongly with each other, as well as with Mercury and Venus. As a result, by themselves, their spin axes would precess with the same rate as the orbital oscillation, which may cause large variations in their axial tilt. Fortunately, the Moon keeps Earth's variations in check. The Moon increases our planet's spin axis precession rate and makes it differ from the orbital oscillation rate. Mars, on the other hand, doesn't have a large enough satellite to stabilize its axial tilt.

"It appears that both exoplanets are very different from Mars and the Earth because they have a weaker connection with their sibling planets," said Li, a faculty member in the School of Physics.

"We don't know whether they possess moons, but our calculations show that even without satellites, the spin axes of Kepler-186f and 62f would have remained constant over tens of millions of years."

Kepler-186f is less than 10 percent larger in radius than Earth, but its mass, composition, and density remain a mystery. It orbits its host star every 130 days. According to NASA, the brightness of that star at high noon, while standing on 186f, would appear as bright as the sun just before sunset here on Earth. Kepler-186f is located in the constellation Cygnus as part of a five-planet star system.

Kepler-62f was the most Earth-like exoplanet until scientists noticed 186f in 2014. It's about 40 percent larger than our planet and is likely a terrestrial or ocean-covered world. It's in the constellation Lyra and is the outermost planet among five exoplanets orbiting a single star.

That's not to say either exoplanet has water, let alone life. But both are relatively good candidates.

"Our study is among the first to investigate climate stability of exoplanets and adds to the growing understanding of these potentially habitable nearby worlds," said Li.

"I don't think we understand enough about the origin of life to rule out the possibility of its presence on planets with irregular seasons," added the CfA’s Shan. "Even on Earth, life is remarkably diverse and has shown incredible resilience in extraordinarily hostile environments.

"But a climatically stable planet might be a more comfortable place to start."

A paper describing these results appeared in the May 17, 2018 issue of The Astronomical Journal.

(This release was originally issued by Georgia Tech.)

Headquartered

in Cambridge, Mass., the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

(CfA) is a collaboration between the Smithsonian Astrophysical

Observatory and the Harvard College Observatory. CfA scientists,

organized into six research divisions, study the origin, evolution and

ultimate fate of the universe.

For more information, contact:

Megan Watzke

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

+1 617-496-7998

mwatzke@cfa.harvard.edu

Peter Edmonds

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

+1 617-571-7279

pedmonds@cfa.harvard.edu