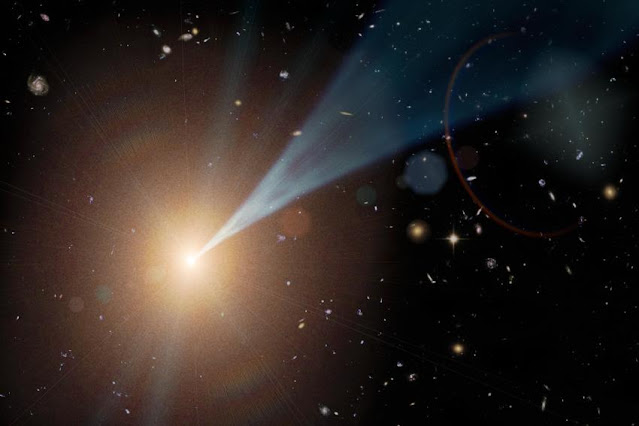

A supercomputer simulation of a galaxy protocluster similar to

costco-i that is surrounded by hot gas (yellow) boiling amid an

intergalactic medium filled with much cooler gas (blue). Credit: The Three Hundred Collaboration

Maunakea, Hawaiʻi – Astrophysicists

using W. M. Keck Observatory on Maunakea in Hawaiʻi have discovered a

galaxy protocluster in the early universe surrounded by gas that is

surprisingly hot.

This scorching gas hugs a region that consists of a giant collection

of galaxies called COSTCO-I. Observed when the universe was 11 billion

years younger, COSTCO-I dates back to a time when the gas that filled

most of the space outside of visible galaxies, called the intergalactic

medium, was significantly cooler. During this era, known as ‘Cosmic

Noon,’ galaxies in the universe were at the peak of forming stars; their

stable environment was full of the cold gas they needed to form and grow, with temperatures measuring around 10,000 degrees Celsius.

In contrast, the cauldron of gas associated with COSTCO-I seems ahead

of its time, roasting in a hot, complex state; its temperatures

resemble the present-day intergalactic medium, which sear from 100,000

to over 10 million degrees Celsius, often called the ‘Warm-Hot

Intergalactic Medium’ (WHIM).

This discovery marks the first time astrophysicists have identified a

patch of ancient gas showing characteristics of the modern-day

intergalactic medium; it is by far the earliest known part of the

universe that’s boiled up to temperatures of today’s WHIM.

The research, which is led by a team from the Kavli Institute for the

Physics and Mathematics of the Universe (Kavli IPMU, part of the

University of Tokyo), is published in today’s issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

A simulated visualization depicts the scenario of large-scale heating

around a galaxy protocluster, using data from supercomputer simulations.

This is believed to be a similar scenario to that observed in the

COSTCO-I protocluster. The yellow area in the center of the picture

represents a huge, hot gas blob spanning several million light years.

The blue color indicates cooler gas located in the outer regions of the

protocluster and the filaments connecting the hot gas with other

structures. The white points embedded within the gas distribution is

light emitted from stars. Simulation Credit: The THREE HUNDRED

Collaboration

“If we think about the present-day intergalactic medium as a gigantic

cosmic stew that is boiling and frothing, then COSTCO-I is probably the

first bubble that astronomers have observed, during an era in the

distant past when most of the pot was still cold,” said Khee-Gan Lee, an

assistant professor at Kavli IPMU and co-author of the paper.

The team observed COSTCO-I when the universe was only a quarter of

its present age. The galaxy protocluster has a total mass of over 400

trillion times the mass of our Sun and spans several million light

years.

While astronomers are now regularly discovering such distant galaxy

protoclusters, the team found something strange when they checked the

ultraviolet spectra covering COSTCO-I’s region using Keck Observatory’s

Low Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (LRIS). Normally, the large mass and

size of galaxy protoclusters would cast a shadow when viewed in the

wavelengths specific to neutral hydrogen associated with the

protocluster gas.

No such absorption shadow was found at the location of COSTCO-I.

“We were surprised because hydrogen absorption is one of the common

ways to search for galaxy protoclusters, and other protoclusters near

COSTCO-I do show this absorption signal,” said Chenze Dong, a Master’s

degree student at the University of Tokyo and lead author of the study.

“The sensitive ultraviolet capabilities of LRIS on the Keck I Telescope

allowed us to make hydrogen gas maps with high confidence, and the

signature of COSTCO-I simply wasn’t there.”

The absence of neutral hydrogen tracing the protocluster implies the

gas in the protocluster must be heated to possibly million-degree

temperatures, far above the cool state expected for the intergalactic

medium at that distant epoch.

This

figure compares observed hydrogen absorption in vicinity of the

COSTCO-I galaxy protocluster (top panel), compared with the expected

absorption given the presence of the protocluster as computed from

computer simulations. Strong hydrogen absorption is shown in red, lower

while weak absorption is shown in blue, and intermediate absorption is

denoted as green or yellow colors. The black dots in the figure show

where astronomers have detected galaxies in that area. At the position

of COSTCO-I (with its center marked as a star in both panels),

astronomers found that the observed hydrogen absorption is not of much

different from the mean value of the universe at that epoch. This is

surprising because one would expect to find extended hydrogen absorption

spanning millions of light years in that region corresponding to the

high observed concentration of galaxies. This figure is adapted from the

Dong et al. 2023 Astrophysical Journal Letters article. Credit: Dong et

al.

“The properties and origin of the WHIM remains one of the biggest

questions in astrophysics right now. To be able to glimpse at one of the

early heating sites of the WHIM will help reveal the mechanisms that

caused the intergalactic gas to boil up into the present-day froth,”

said Lee. “There are a few possibilities for how this can happen, but it

might be either from gas heating up as they collide with each other

during gravitational collapse, or giant radio jets might be pumping

energy from supermassive black holes within the protocluster.”

The intergalactic medium serves as the gas reservoir that feeds raw

material into galaxies. Hot gas behaves differently from cold gas, which

determines how easily they can stream into galaxies to form stars. As

such, having the ability to directly study the growth of the WHIM in the

early universe enables astronomers to build up a coherent picture of

galaxy formation and the lifecycle of gas that fuels it.

Source: W. M. Keck Observatory

About LRIS

The Low Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (LRIS) is a very versatile

and ultra-sensitive visible-wavelength imager and spectrograph built at

the California Institute of Technology by a team led by Prof. Bev Oke

and Prof. Judy Cohen and commissioned in 1993. Since then it has seen

two major upgrades to further enhance its capabilities: the addition of a

second, blue arm optimized for shorter wavelengths of light and the

installation of detectors that are much more sensitive at the longest

(red) wavelengths. Each arm is optimized for the wavelengths it

covers. This large range of wavelength coverage, combined with the

instrument’s high sensitivity, allows the study of everything from

comets (which have interesting features in the ultraviolet part of the

spectrum), to the blue light from star formation, to the red light of

very distant objects. LRIS also records the spectra of up to 50 objects

simultaneously, especially useful for studies of clusters of galaxies in

the most distant reaches, and earliest times, of the universe. LRIS was

used in observing distant supernovae by astronomers who received the

Nobel Prize in Physics in 2011 for research determining that the

universe was speeding up in its expansion.

About W. M. Keck Observatory

The W. M. Keck Observatory telescopes are among the most

scientifically productive on Earth. The two 10-meter optical/infrared

telescopes atop Maunakea on the Island of Hawaii feature a suite of

advanced instruments including imagers, multi-object spectrographs,

high-resolution spectrographs, integral-field spectrometers, and

world-leading laser guide star adaptive optics systems. Some of the data

presented herein were obtained at Keck Observatory, which is a private

501(c) 3 non-profit organization operated as a scientific partnership

among the California Institute of Technology, the University of

California, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The

Observatory was made possible by the generous financial support of the

W. M. Keck Foundation. The authors wish to recognize and acknowledge the

very significant cultural role and reverence that the summit of

Maunakea has always had within the Native Hawaiian community. We are

most fortunate to have the opportunity to conduct observations from this

mountain..