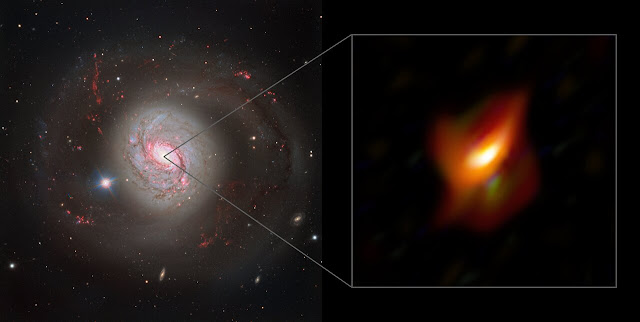

Galaxy Messier 77 and close-up view of its active centre

A close-up view of Messier 77’s active galactic nucleus

Dazzling galaxy Messier 77

Artist’s impression of the active galactic nucleus of Messier 77

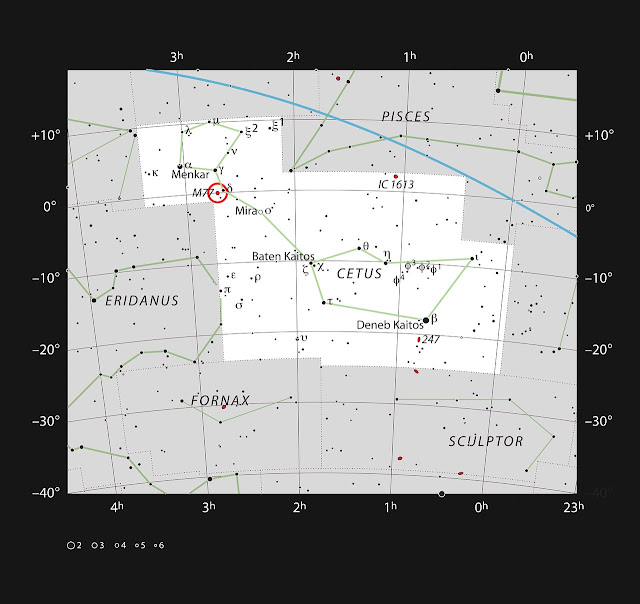

The active galaxy Messier 77 in the constellation of Cetus

Wide-field image of the sky around Messier 77

Video

Artist’s animation of the active galactic nucleus of Messier 77

The Unified Model of active galactic nuclei

The European Southern Observatory’s Very

Large Telescope Interferometer (ESO’s VLTI) has observed a cloud of

cosmic dust at the centre of the galaxy Messier 77 that is hiding a

supermassive black hole. The findings have confirmed predictions made

around 30 years ago and are giving astronomers new insight into “active

galactic nuclei”, some of the brightest and most enigmatic objects in

the universe.

Active galactic nuclei

(AGNs) are extremely energetic sources powered by supermassive black

holes and found at the centre of some galaxies. These black holes feed

on large volumes of cosmic dust and gas. Before it is eaten up, this

material spirals towards the black hole and huge amounts of energy are

released in the process, often outshining all the stars in the galaxy.

Astronomers have been curious about AGNs ever since they first

spotted these bright objects in the 1950s. Now, thanks to ESO’s VLTI, a

team of researchers, led by Violeta Gámez Rosas from Leiden University

in the Netherlands, have taken a key step towards understanding how they

work and what they look like up close. The results are published today

in Nature.

By making extraordinarily detailed observations of the centre of the galaxy Messier 77,

also known as NGC 1068, Gámez Rosas and her team detected a thick ring

of cosmic dust and gas hiding a supermassive black hole. This discovery

provides vital evidence to support a 30-year-old theory known as the

Unified Model of AGNs.

Astronomers know there are different types of AGN. For example, some

release bursts of radio waves while others don’t; certain AGNs shine

brightly in visible light, while others, like Messier 77, are more

subdued. The Unified Model states that despite their differences, all

AGNs have the same basic structure: a supermassive black hole surrounded

by a thick ring of dust.

According to this model, any difference in appearance between AGNs

results from the orientation at which we view the black hole and its

thick ring from Earth. The type of AGN we see depends on how much the

ring obscures the black hole from our view point, completely hiding it

in some cases.

Astronomers had found some evidence to support the Unified Model

before, including spotting warm dust at the centre of Messier 77.

However, doubts remained about whether this dust could completely hide a

black hole and hence explain why this AGN shines less brightly in

visible light than others.

“The real nature of the dust clouds and their role in both

feeding the black hole and determining how it looks when viewed from

Earth have been central questions in AGN studies over the last three

decades,” explains Gámez Rosas. “Whilst no single result will settle all the questions we have, we have taken a major step in understanding how AGNs work.”

The observations were made possible thanks to the Multi AperTure mid-Infrared SpectroScopic Experiment (MATISSE) mounted on ESO’s VLTI,

located in Chile’s Atacama Desert. MATISSE combined infrared light

collected by all four 8.2-metre telescopes of ESO’s Very Large Telescope

(VLT) using a technique called interferometry. The team used MATISSE to

scan the centre of Messier 77, located 47 million light-years away in

the constellation Cetus.

“MATISSE can see a broad range of infrared wavelengths, which

lets us see through the dust and accurately measure temperatures.

Because the VLTI is in fact a very large interferometer, we have the

resolution to see what’s going on even in galaxies as far away as

Messier 77. The images we obtained detail the changes in temperature and

absorption of the dust clouds around the black hole,” says co-author Walter Jaffe, a professor at Leiden University.

Combining the changes in dust temperature (from around room

temperature to about 1200 °C) caused by the intense radiation from the

black hole with the absorption maps, the team built up a detailed

picture of the dust and pinpointed where the black hole must lie. The

dust — in a thick inner ring and a more extended disc — with the black

hole positioned at its centre supports the Unified Model. The team also

used data from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array,

co-owned by ESO, and the National Radio Astronomy Observatory’s Very

Long Baseline Array to construct their picture.

“Our results should lead to a better understanding of the inner workings of AGNs,” concludes Gámez Rosas. “They

could also help us better understand the history of the Milky Way,

which harbours a supermassive black hole at its centre that may have

been active in the past.”

The researchers are now looking to use ESO’s VLTI to find more

supporting evidence of the Unified Model of AGNs by considering a larger

sample of galaxies.

Team member Bruno Lopez, the MATISSE Principal Investigator at the Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur in Nice, France, says: “Messier

77 is an important prototype AGN and a wonderful motivation to expand

our observing programme and to optimise MATISSE to tackle a wider sample

of AGNs."

ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT),

set to begin observing later this decade, will also aid the search,

providing results that will complement the team’s findings and allow

them to explore the interaction between AGNs and galaxies.

More Information This research was presented in the paper “Thermal imaging of dust hiding the black hole in the Active Galaxy NGC 1068” (doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04311-7) to appear in Nature.

The team is composed of Violeta Gámez Rosas (Leiden Observatory,

Leiden University, Netherlands [Leiden]), Jacob W. Isbell (Max Planck

Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg, Germany [MPIA]), Walter Jaffe

(Leiden), Romain G. Petrov (Université Côte d’Azur, Observatoire de la

Côte d’Azur, CNRS, Laboratoire Lagrange, France [OCA]), James H. Leftley

(OCA), Karl-Heinz Hofmann (Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy,

Bonn, Germany [MPIfR]), Florentin Millour (OCA), Leonard Burtscher

(Leiden), Klaus Meisenheimer (MPIA), Anthony Meilland (OCA), Laurens B.

F. M. Waters (Department of Astrophysics/IMAPP, Radboud University, the

Netherlands; SRON, Netherlands Institute for Space Research, the

Netherlands), Bruno Lopez (OCA), Stéphane Lagarde (OCA), Gerd Weigelt

(MPIfR), Philippe Berio (OCA), Fatme Allouche (OCA), Sylvie Robbe-Dubois

(OCA), Pierre Cruzalèbes (OCA), Felix Bettonvil (ASTRON, Dwingeloo, the

Netherlands [ASTRON]), Thomas Henning (MPIA), Jean-Charles Augereau

(Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, Institute for Planetary sciences and

Astrophysics, France [IPAG]), Pierre Antonelli (OCA), Udo Beckmann

(MPIfR), Roy van Boekel (MPIA), Philippe Bendjoya (OCA), William C.

Danchi (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, USA), Carsten

Dominik (Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy, University of

Amsterdam, The Netherlands [API]), Julien Drevon (OCA), Jack F.

Gallimore (Department of Physics and Astronomy, Bucknell University,

Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, USA), Uwe Graser (MPIA), Matthias Heininger

(MPIfR), Vincent Hocdé (OCA), Michiel Hogerheijde (Leiden; API), Josef

Hron (Department of Astrophysics, University of Vienna, Austria),

Caterina M.V. Impellizzeri (Leiden), Lucia Klarmann (MPIA), Elena

Kokoulina (OCA), Lucas Labadie (1st Institute of Physics, University of

Cologne, Germany), Michael Lehmitz (MPIA), Alexis Matter (OCA), Claudia

Paladini (European Southern Observatory, Santiago, Chile [ESO-Chile]),

Eric Pantin (Centre d'Etudes de Saclay, Gif-sur-Yvette, France),

Jörg-Uwe Pott (MPIA), Dieter Schertl (MPIfR), Anthony Soulain (Sydney

Institute for Astronomy, University of Sydney, Australia [SIfA]),

Philippe Stee (OCA), Konrad Tristram (ESO-Chile), Jozsef Varga (Leiden),

Julien Woillez (European Southern Observatory, Garching bei München,

Germany [ESO]), Sebastian Wolf (Institute for Theoretical Physics and

Astrophysics, University of Kiel, Germany), Gideon Yoffe (MPIA), and

Gerard Zins (ESO-Chile).

MATISSE was designed, funded and built in close collaboration with

ESO, by a consortium composed of institutes in France (J.-L. Lagrange

Laboratory — INSU-CNRS — Côte d’Azur Observatory — University of Nice

Sophia-Antipolis), Germany (MPIA, MPIfR and University of Kiel), the

Netherlands (NOVA and University of Leiden), and Austria (University of

Vienna). The Konkoly Observatory and Cologne University have also

provided some support in the manufacture of the instrument.

The European Southern Observatory (ESO) enables scientists worldwide

to discover the secrets of the Universe for the benefit of all. We

design, build and operate world-class observatories on the ground —

which astronomers use to tackle exciting questions and spread the

fascination of astronomy — and promote international collaboration in

astronomy. Established as an intergovernmental organisation in 1962,

today ESO is supported by 16 Member States (Austria, Belgium, the Czech

Republic, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the

Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United

Kingdom), along with the host state of Chile and with Australia as a

Strategic Partner. ESO’s headquarters and its visitor centre and

planetarium, the ESO Supernova, are located close to Munich in Germany,

while the Chilean Atacama Desert, a marvellous place with unique

conditions to observe the sky, hosts our telescopes. ESO operates three

observing sites: La Silla, Paranal and Chajnantor. At Paranal, ESO

operates the Very Large Telescope and its Very Large Telescope

Interferometer, as well as two survey telescopes, VISTA working in the

infrared and the visible-light VLT Survey Telescope. Also at Paranal ESO

will host and operate the Cherenkov Telescope Array South, the world’s

largest and most sensitive gamma-ray observatory. Together with

international partners, ESO operates APEX and ALMA on Chajnantor, two

facilities that observe the skies in the millimetre and submillimetre

range. At Cerro Armazones, near Paranal, we are building “the world’s

biggest eye on the sky” — ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope. From our

offices in Santiago, Chile we support our operations in the country and

engage with Chilean partners and society.

Links

Contacts:

Violeta Gámez Rosas

Leiden University

Leiden, the Netherlands

Tel: +31 71 527 5737

Email: gamez@strw.leidenuniv.nl

Walter Jaffe

Leiden University

Leiden, the Netherlands

Tel: +31 71 527 5737

Email: jaffe@strw.leidenuniv.nl

Bruno Lopez

MATISSE Principal Investigator

Observatoire de la Côte d’ Azur, Nice, France

Tel: +33 4 92 00 30 11

Email: Bruno.Lopez@oca.eu

Romain Petrov

MATISSE Project Scientist

Observatoire de la Côte d’ Azur, Nice, France

Tel: +33 4 92 00 30 11

Email: Romain.Petrov@oca.eu

Bárbara Ferreira

ESO Media Manager

Garching bei München, Germany

Tel: +49 89 3200 6670

Cell: +49 151 241 664 00

Email: press@eso.org

Source: ESO/News