Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/INAF/M.Guarcello et al.; Optical: NASA/STScI

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/INAF/M.Guarcello et al.; Optical: NASA/STScI

Optical and infrared identifications with stars were used to sort out

chance interlopers in the foreground or background, and to determine

that more than two-thirds of the sources are likely young stars that are

members of the NGC 6611 cluster.

Chandra's unique ability to resolve and locate X-ray sources made it

possible to identify hundreds of very young stars, and those still in

the process of forming (known as "protostars"). Infrared observations

from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope and the European Southern

Observatory indicate that 219 of the X-ray sources in the Eagle Nebula

are young stars surrounded by disks of dust and gas and 964 are young

stars without these disks.

Combined with the Chandra

observations, the data show that X-ray activity in young stars with

disks is, on average, a few times less intense that in young stars

without disks. This behavior is likely due to the interaction of the

disk with the magnetic field of the host star. Much of the matter in the

disks around these protostars will eventually be blown away by

radiation from their host stars, but, in certain cases, some of it may

form into planets.

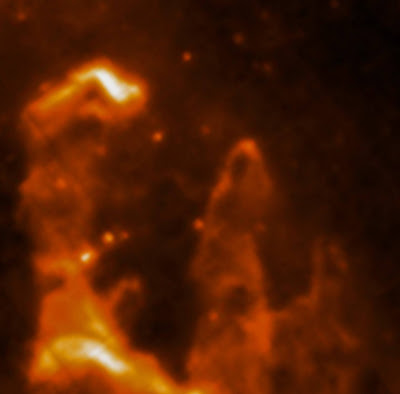

This new composite image shows the region around the Pillars, which are about 5,700 light years

from Earth. The image combines X-ray data from NASA's Chandra X-ray

Observatory and Hubble Space Telescope optical data. The optical image,

taken with filters to emphasize the interstellar gas and dust, shows

dusty brown nebula immersed in a blue-green haze, and a few stars that

appear as pink dots in the image. The Chandra data reveal X-rays from

hot outer atmospheres from stars. In this image, low, medium, and

high-energy X-rays detected by Chandra have been colored red, green, and

blue.

In the image, some of the X-ray sources appear to be located in the

Pillars. However, an analysis of the absorption of X-rays from these

sources indicates that almost all of these sources belong to the larger

Eagle Nebula rather than being immersed in the Pillars.

Three X-ray sources appear to lie near the tip of the largest Pillar.

Infrared observations show a protostar containing four or five times

the mass of the Sun is located near one of these sources — the blue one

near the tip of the Pillar. This source exhibits strong absorption of

low-energy X-rays, consistent with a location inside the Pillar. Similar

arguments show that one of these sources is associated with a disk-less

star outside the Pillar, and one is a foreground object.

A paper by Mario Guarcello, currently at the National Institute for Astronomy in Italy, and colleagues describing these results appeared in The Astrophysical Journal.

NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, manages the

Chandra program for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington.

The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts,

controls Chandra's science and flight operations.

Fast Facts for The Eagle Nebula (M16):

Scale: Image is about 2.5 arcmin (5.13 light years across) across

Category: Normal Stars & Star Clusters

Coordinates (J2000): RA 18h 18m 51.79s | Dec -13º 49' 54.93"

Constellation: Serpens

Observation Date: 07/30/2001

Observation Time: 22 hours

Obs. ID: 978

Instrument: ACIS

References: M. Guarcello et al. 2012, ApJ, 753, 117; arXiv:1205.2111

Color Code: X-ray (larger point sources): Red (0.5-1.5 keV); Green (1.5-2.5 keV); Blue (2.5-7.0 keV); Optical (diffuse emission & smaller point sources): Red, Green and Blue

Distance Estimate: About 5,700 light years

Source: NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory