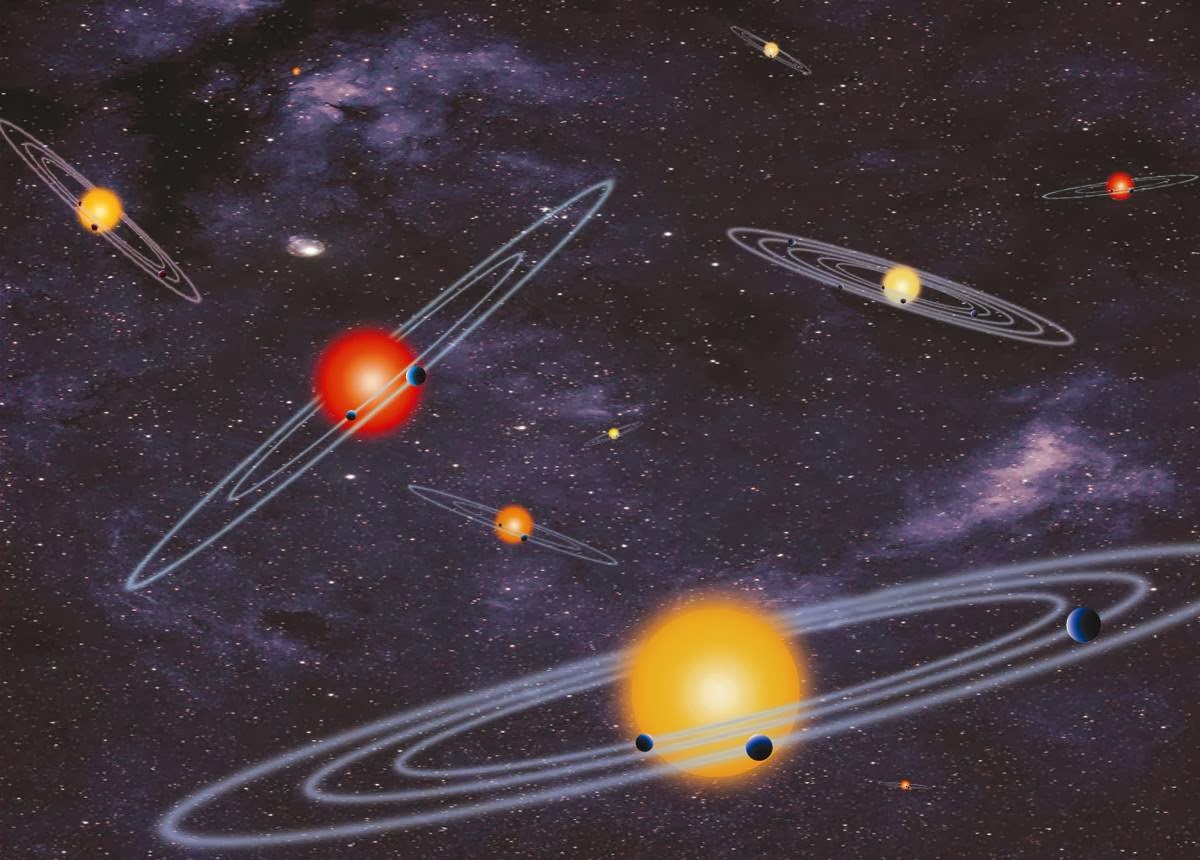

The artist concept depicts multiple-transiting planet systems, which are stars with more than one planet. The planets eclipse or transit their host star from the vantage point of the observer. This angle is called edge-on.

Image Credit:

NASA

NASA's

Kepler mission announced Wednesday the discovery of 715 new planets.

These newly-verified worlds orbit 305 stars, revealing multiple-planet

systems much like our own solar system.

Nearly 95 percent of these planets are smaller than Neptune, which is

almost four times the size of Earth.

This discovery marks a significant

increase in the number of known small-sized planets more akin to Earth

than previously identified exoplanets, which are planets outside our

solar system.

"The Kepler team continues to amaze and excite us with their planet

hunting results," said John Grunsfeld, associate administrator for

NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. "That these new

planets and solar systems look somewhat like our own, portends a great

future when we have the James Webb Space Telescope in space to

characterize the new worlds.”

Since the discovery of the first planets outside our solar system

roughly two decades ago, verification has been a laborious

planet-by-planet process. Now, scientists have a statistical technique

that can be applied to many planets at once when they are found in

systems that harbor more than one planet around the same star.

To verify this bounty of planets, a research team co-led by Jack

Lissauer, planetary scientist at NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett

Field, Calif., analyzed stars with more than one potential planet, all

of which were detected in the first two years of Kepler's observations

-- May 2009 to March 2011.

The research team used a technique called verification by

multiplicity, which relies in part on the logic of probability. Kepler

observes 150,000 stars, and has found a few thousand of those to have

planet candidates. If the candidates were randomly distributed among

Kepler's stars, only a handful would have more than one planet

candidate. However, Kepler observed hundreds of stars that have multiple

planet candidates. Through a careful study of this sample, these 715

new planets were verified.

This method can be likened to the behavior we know of lions and

lionesses. In our imaginary savannah, the lions are the Kepler stars and

the lionesses are the planet candidates. The lionesses would sometimes

be observed grouped together whereas lions tend to roam on their own. If

you see two lions it could be a lion and a lioness or it could be two

lions. But if more than two large felines are gathered, then it is very

likely to be a lion and his pride. Thus, through multiplicity the

lioness can be reliably identified in much the same way multiple planet

candidates can be found around the same star.

"Four years ago, Kepler began a string of announcements of first

hundreds, then thousands, of planet candidates --but they were only

candidate worlds," said Lissauer. "We've now developed a process to

verify multiple planet candidates in bulk to deliver planets wholesale,

and have used it to unveil a veritable bonanza of new worlds."

These multiple-planet systems are fertile grounds for studying

individual planets and the configuration of planetary neighborhoods.

This provides clues to planet formation.

Four of these new planets are less than 2.5 times the size of Earth

and orbit in their sun's habitable zone, defined as the range of

distance from a star where the surface temperature of an orbiting planet

may be suitable for life-giving liquid water.

One of these new habitable zone planets, called Kepler-296f, orbits a

star half the size and 5 percent as bright as our sun. Kepler-296f is

twice the size of Earth, but scientists do not know whether the planet

is a gaseous world, with a thick hydrogen-helium envelope, or it is a

water world surrounded by a deep ocean.

"From this study we learn planets in these multi-systems are small

and their orbits are flat and circular -- resembling pancakes -- not

your classical view of an atom," said Jason Rowe, research scientist at

the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif., and co-leader of the

research. "The more we explore the more we find familiar traces of

ourselves amongst the stars that remind us of home."

This latest discovery brings the confirmed count of planets outside

our solar system to nearly 1,700. As we continue to reach toward the

stars, each discovery brings us one step closer to a more accurate

understanding of our place in the galaxy.

Launched in March 2009, Kepler is the first NASA mission to find

potentially habitable Earth-size planets. Discoveries include more than

3,600 planet candidates, of which 961 have been verified as bona-fide

worlds.

The findings papers will be published March 10 in The Astrophysical Journal and are available for download at: http://www.nasa.gov/ames/kepler/digital-press-kit-kepler-planet-bonanza

Ames is responsible for the Kepler mission concept, ground system

development, mission operations and science data analysis. NASA's Jet

Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., managed Kepler mission

development. Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp. in Boulder, Colo.,

developed the Kepler flight system and supports mission operations with

the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of

Colorado in Boulder. The Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore

archives, hosts and distributes Kepler science data. Kepler is NASA's

10th Discovery Mission and was funded by the agency's Science Mission

Directorate.

For more information about the Kepler space telescope, visit: http://www.nasa.gov/kepler

Michele Johnson

Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, Calif.

650-604-6982

michele.johnson@nasa.gov

J.D. Harrington

Headquarters, Washington

202-358-5241

j.d.harrington@nasa.gov

Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, Calif.

650-604-6982

michele.johnson@nasa.gov

J.D. Harrington

Headquarters, Washington

202-358-5241

j.d.harrington@nasa.gov