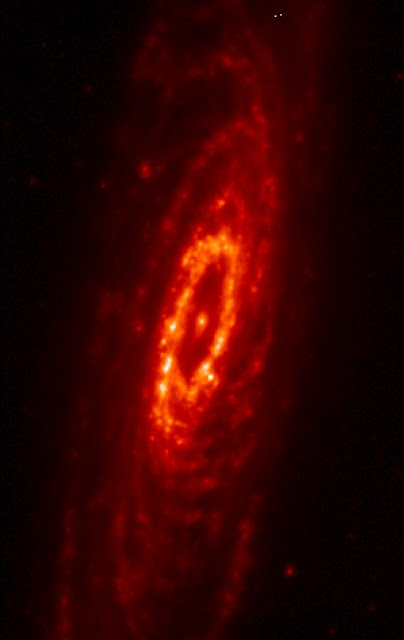

Spiral Galaxy, NGC 7331

Image credit: Adam Block/Mount Lemmon SkyCenter/University of Arizona/Sutter et al., 2021.

Image credit: Adam Block/Mount Lemmon SkyCenter/University of Arizona/Sutter et al., 2021.

NGC 7331 taken in infrared light by the Spitzer Space Telescope. The central ring is the brightest feature of this galaxy in the infrared, indicating that it is permeated by dust that has been warmed by young stars. Image credit: NASA

Columbia, MD—January 10, 2022. Ionized carbon is an important tracer of astronomical processes, and understanding how the angle of a galaxy affects the observation of ionized carbon can be key for improving analyses of such processes.

Because the effects of observing perspective are complex, spiral galaxies tend to only be studied if their orientation is just right, that is, if telescopes can see them face-on rather than at an angle. Now, a study of the galaxy NGC 7331 with the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), NASA's airborne observatory has begun to characterize these effects.

Universities Space Research Association’s Jessica Sutter, the lead author of the study, investigated the various factors that can affect ionized carbon emission from a galaxy, including the galaxy’s angle of inclination. Her presentation, “A Map of the Molecular Ring and Arms of a Spiral Galaxy,” at the American Astronomical Society’s Virtual Press Conference will take place on January 10 at 10:15 AM Mountain Time. A paper on this topic has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

“One of the reasons more people haven’t looked at ionized carbon emission from edge-on galaxies is because one can’t do it from ground observations. You need an observing platform at least from the stratosphere, if not in space,” Sutter said. “With SOFIA, we have some more opportunities to get these full maps, and we’re seeing how useful that may be.”

Ionized carbon is an important measurement in astronomy, as it can indicate the presence of star formation, the cooling of the space between stars, and other processes. Moreover, it tends to be quite bright, making it easily detectable in galaxies tens of billions of lightyears away, which is especially useful for galaxies with little other data available.

“Knowing where the ionized carbon emission is coming from – whether photodissociation regions, or ionized hydrogen regions, or diffuse ionized gas – is going to affect how we might use it to trace molecular gas, or star formation, or photodissociation conditions,” Sutter said. “Our observing angle may have an effect.”

Because NGC 7331 is an inclined galaxy, the fraction of ionized carbon observed varied depending on which side of the galaxy was being observed. This should be a significant consideration for researchers, especially if they aren’t sure of the inclination angle of the galaxy they are studying.

"With the help of SOFIA’s unique ability to study ionized carbon from within the Earth’s stratosphere, we hope to expand this analysis by mapping ionized carbon emission from an additional set of galaxies, " said Sutter. This will help uncover how inclination and other structural factors impact the charged atom’s importance in analyses, helping demystify the history of the universe.

Because the effects of observing perspective are complex, spiral galaxies tend to only be studied if their orientation is just right, that is, if telescopes can see them face-on rather than at an angle. Now, a study of the galaxy NGC 7331 with the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), NASA's airborne observatory has begun to characterize these effects.

Universities Space Research Association’s Jessica Sutter, the lead author of the study, investigated the various factors that can affect ionized carbon emission from a galaxy, including the galaxy’s angle of inclination. Her presentation, “A Map of the Molecular Ring and Arms of a Spiral Galaxy,” at the American Astronomical Society’s Virtual Press Conference will take place on January 10 at 10:15 AM Mountain Time. A paper on this topic has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

“One of the reasons more people haven’t looked at ionized carbon emission from edge-on galaxies is because one can’t do it from ground observations. You need an observing platform at least from the stratosphere, if not in space,” Sutter said. “With SOFIA, we have some more opportunities to get these full maps, and we’re seeing how useful that may be.”

Ionized carbon is an important measurement in astronomy, as it can indicate the presence of star formation, the cooling of the space between stars, and other processes. Moreover, it tends to be quite bright, making it easily detectable in galaxies tens of billions of lightyears away, which is especially useful for galaxies with little other data available.

“Knowing where the ionized carbon emission is coming from – whether photodissociation regions, or ionized hydrogen regions, or diffuse ionized gas – is going to affect how we might use it to trace molecular gas, or star formation, or photodissociation conditions,” Sutter said. “Our observing angle may have an effect.”

Because NGC 7331 is an inclined galaxy, the fraction of ionized carbon observed varied depending on which side of the galaxy was being observed. This should be a significant consideration for researchers, especially if they aren’t sure of the inclination angle of the galaxy they are studying.

"With the help of SOFIA’s unique ability to study ionized carbon from within the Earth’s stratosphere, we hope to expand this analysis by mapping ionized carbon emission from an additional set of galaxies, " said Sutter. This will help uncover how inclination and other structural factors impact the charged atom’s importance in analyses, helping demystify the history of the universe.

SOFIA is a joint project of NASA and the German Space Agency, DLR. DLR provides the telescope, scheduled aircraft maintenance, and other support for the mission. NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley manages the SOFIA program, science, and mission operations in cooperation with the Universities Space Research Association, headquartered in Columbia, Maryland, and the German SOFIA Institute at the University of Stuttgart. The aircraft is maintained and operated by NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center Building 703, in Palmdale, California.

About USRA

Founded in 1969, under the auspices of the National Academy of Sciences at the request of the U.S. Government, the Universities Space Research Association (USRA) is a nonprofit corporation chartered to advance space-related science, technology, and engineering. USRA operates scientific institutes and facilities, and conducts other major research and educational programs, under Federal funding. USRA engages the university community and employs in-house scientific leadership, innovative research and development, and project management expertise. More information about USRA is available at www.usra.edu.