The B5 complex (red and green; radio images taken with the VLA and GBT) seen within its neighborhood, embedded in dust (blue) as seen with ESA’s Herschel Space Observatory, in infrared light. Credit: B. Saxton (NRAO/AUI/NSF); ESA

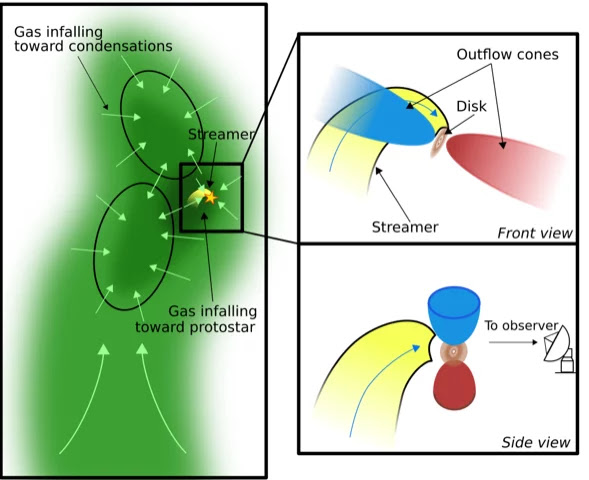

This diagram shows the gas flow in the Barnard 5 region at the different scales investigated in this work. At the left, fresh gas moves inside the filaments toward condensations (black contours) and the protostar (yellow star) in the direction indicated by the light green arrows. The yellow curve shows the streamer transporting material towards the protostellar disk. The right images zoom into the streamer (yellow), as well as the two outflows (red and blue) and the protostellar disk (brown). The top right schematics shows the front view; the bottom right schematics is rotated by 90° to observe the streamer unobstructed by the outflow cone. © MPE

This plot shows the central velocities for two components, where gas is falling towards the protostar (black star). The two colourbars to the right indicate the velocities of the blueshifted and redshifted clusters, respectively. While a streamline model confirmed that the blueshifted cluster is indeed a streamer transporting gas to the protostar, the classification of the red component as a “streamer" is tentative for now. © MPE

A recent study led by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics challenges conventional notions of star formation by revealing the intricate connection between streamers and filaments. Focusing on the star-forming region Barnard 5, the study traces the journey of material from larger scales to protostellar disks, uncovering a remarkable relationship between elongated filaments and gas streamers. In particular, the team discovered a sizeable streamer, which suggests that young stars can receive additional material even after the so-believed main accretion phase.

Contacts:

Maria Teresa Valdivia Mena

phd student

tel: +49 89 30000-3546

tel: +49 89 30000-3950

mvaldivi@mpe.mpg.de

Jaime Pineda Fornerod

scientist

tel: +49 89 30000-3610

tel: +49 173 3517084

tel: +49 89 30000-3950

jpineda@mpe.mpg.de

Hannelore Hämmerle

press officer

tel> +49 89 30000-3980

tel: +49 89 30000-3569

hanneh@mpe.mpg.de

Original publication

M. T. Valdivia-Mena, J. E. Pineda, D. M. Segura-Cox, P. Caselli, A. Schmiedeke, S. Choudhury, S. S. R. Offner, R. Neri, A. Goodman, G. A. Fuller

Flow of gas detected from beyond the filaments to protostellar scales in Barnard 5

A&A, 677, A92 (2023

Source

Traditionally, star formation has been associated with the gradual accumulation of material within natal envelopes, cool and dense regions in the larger molecular cloud. Once the core density reaches a certain limit, it will collapse and form a proto-star. While the protostar continues to accrete material from the newly formed circumstellar disk around it, the classical picture considers this core region as an isolated unit. In recent years, however, there has been an explosion in the discovery of streamers, channels that can surpass the limits of the envelope, with lengths up to 10 000 AU (approximately 0.15 light years). These streamers nourish the disk with fresh gas, but it is still uncertain where they originate. For the first time, researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE) have now found clues of a connection between streamers and filaments in star-forming regions, offering a new perspective on the birth of stars.

The team focused on the Barnard 5 region (B5), a dense molecular cloud in the constellation of Perseus. In Barnard 5, two filaments harbour a lonely protostar – but not for long: there are three other condensations that will become a bounded multiple star system in the future. With the combination of three powerful instruments, ALMA in the Chilean desert, NOEMA in the French Alps and the IRAM 30m telescope in Pico Veleta, Spain, the researchers at MPE followed the flow of gas across various scales. “Our aim was to trace the journey of gas from outside of the filament that contains the protostar to the protostellar disks, bridging the gap between different scales of star formation,” says Teresa Valdivia-Mena, PhD student in the Center for Astrochemical Studies at MPE and lead-author of the study.

On larger scales, the researchers found that chemically fresh gas, untainted by the star-formation process, enters the filaments from the bigger Barnard 5 region. The velocity of the gas traced by NOEMA and the 30m IRAM telescope is consistent with infall from outside the two filaments. When the gas reaches the filaments’ spines, it flows in the direction of the three condensations and the protostar. Zooming in with ALMA, the team found a streamer feeding the protostellar disk. What is striking about these observations is that – despite different resolutions – the speed of the chemically fresh gas coming from outside the filaments matches the speed of the streamer. Both the location and the speed along the streamer were reproduced using a theoretical model of free-falling material, and seem to be connected to the flow on larger scales. This means that the chemically unprocessed gas from beyond the filaments can reach the protostar, giving it access to a larger reservoir of material to grow even after the main accretion phase.

“These results are very exciting, because they show that the star-formation process is a multiscale process,” emphasises Jaime Pineda, second author on the Barnard 5 study. “Accretion flows and streamers connect the young stellar objects with the parental cloud. This dynamic process of feeding the young star might even affect the whole disk and planet formation process, although we need future observations to confirm this.” In addition, these observations imply that pristine material from the interstellar cloud can be an important ingredient for the future planetary system. The composition of new-born planets as well as their atmospheres might therefore be influenced by a much larger region than previously assumed.

In essence, this study already paints a vivid picture of the complex dance of gas flows from streamers to filaments and ultimately to protostellar scales. “Our research emphasises how interconnected various scales in the star formation process are, highlighting the profound impact of these flows on the evolution of nascent stars,” concludes Valdivia-Mena.

The team focused on the Barnard 5 region (B5), a dense molecular cloud in the constellation of Perseus. In Barnard 5, two filaments harbour a lonely protostar – but not for long: there are three other condensations that will become a bounded multiple star system in the future. With the combination of three powerful instruments, ALMA in the Chilean desert, NOEMA in the French Alps and the IRAM 30m telescope in Pico Veleta, Spain, the researchers at MPE followed the flow of gas across various scales. “Our aim was to trace the journey of gas from outside of the filament that contains the protostar to the protostellar disks, bridging the gap between different scales of star formation,” says Teresa Valdivia-Mena, PhD student in the Center for Astrochemical Studies at MPE and lead-author of the study.

On larger scales, the researchers found that chemically fresh gas, untainted by the star-formation process, enters the filaments from the bigger Barnard 5 region. The velocity of the gas traced by NOEMA and the 30m IRAM telescope is consistent with infall from outside the two filaments. When the gas reaches the filaments’ spines, it flows in the direction of the three condensations and the protostar. Zooming in with ALMA, the team found a streamer feeding the protostellar disk. What is striking about these observations is that – despite different resolutions – the speed of the chemically fresh gas coming from outside the filaments matches the speed of the streamer. Both the location and the speed along the streamer were reproduced using a theoretical model of free-falling material, and seem to be connected to the flow on larger scales. This means that the chemically unprocessed gas from beyond the filaments can reach the protostar, giving it access to a larger reservoir of material to grow even after the main accretion phase.

“These results are very exciting, because they show that the star-formation process is a multiscale process,” emphasises Jaime Pineda, second author on the Barnard 5 study. “Accretion flows and streamers connect the young stellar objects with the parental cloud. This dynamic process of feeding the young star might even affect the whole disk and planet formation process, although we need future observations to confirm this.” In addition, these observations imply that pristine material from the interstellar cloud can be an important ingredient for the future planetary system. The composition of new-born planets as well as their atmospheres might therefore be influenced by a much larger region than previously assumed.

In essence, this study already paints a vivid picture of the complex dance of gas flows from streamers to filaments and ultimately to protostellar scales. “Our research emphasises how interconnected various scales in the star formation process are, highlighting the profound impact of these flows on the evolution of nascent stars,” concludes Valdivia-Mena.

Contacts:

Maria Teresa Valdivia Mena

phd student

tel: +49 89 30000-3546

tel: +49 89 30000-3950

mvaldivi@mpe.mpg.de

Jaime Pineda Fornerod

scientist

tel: +49 89 30000-3610

tel: +49 173 3517084

tel: +49 89 30000-3950

jpineda@mpe.mpg.de

Hannelore Hämmerle

press officer

tel> +49 89 30000-3980

tel: +49 89 30000-3569

hanneh@mpe.mpg.de

Original publication

M. T. Valdivia-Mena, J. E. Pineda, D. M. Segura-Cox, P. Caselli, A. Schmiedeke, S. Choudhury, S. S. R. Offner, R. Neri, A. Goodman, G. A. Fuller

Flow of gas detected from beyond the filaments to protostellar scales in Barnard 5

A&A, 677, A92 (2023

Source