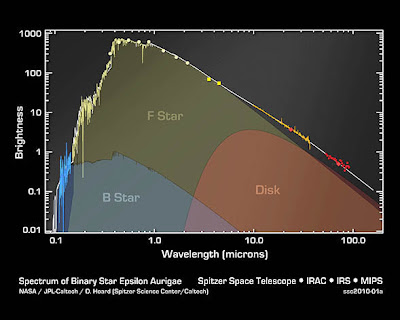

This graph of data from multiple telescopes shows the distribution of light from a pair of stars known as Epsilon Aurigae. For centuries, astronomers had not been able to figure out the nature of this "eclipsing binary system," in which a bright naked-eye star is eclipsed by a companion object every 27 years.

Data from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope are pointing to a solution to this age-old riddle. The Spitzer data, shown in bright yellow and orange, provide the missing puzzle pieces need to fit all the data on the star together into a neat model. The blue data show ultraviolet observations, and the light yellow/green data are from visible-light telescopes. The blue data show light from the companion object, a so-called B star, while the light yellow data show light from the main bright star, called an F star. The orange and bright yellow data from Spitzer show light from the F star and a dusty disk that is surrounding the B-star.

The new model indicates that the F star is not a supergiant as a favored theory had proposed but a dying star with a lot less mass.

Mystery of the Fading Star

For almost two centuries, humans have looked up at a bright star called Epsilon Aurigae and watched with their own eyes as it seemed to disappear into the night sky, slowly fading before coming back to life again. Today, as another dimming of the system is underway, mysteries about the star persist. Though astronomers know that Epsilon Aurigae is eclipsed by a dark companion object every 27 years, the nature of both the star and object has remained unclear.

Now, new observations from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope -- in combination with archived ultraviolet, visible and other infrared data -- point to one of two competing theories, and a likely solution to this age-old puzzle. One theory holds that the bright star is a massive supergiant, periodically eclipsed by two tight-knit stars inside a swirling, dusty disk. The second theory holds that the bright star is in fact a dying star with a lot less mass, periodically eclipsed by just a single star inside a disk. The Spitzer data strongly support the latter scenario.

"We've really shifted the balance of the two competing theories," said Donald Hoard of NASA's Spitzer Science Center at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. "Now we can get busy working out all the details." Hoard presented the results today at the 215th meeting of the American Astronomical Meeting in Washington.

Epsilon Aurigae can be seen at night from the northern hemisphere with the naked eye, even in some urban areas. Last August, it began its roughly two-year dimming, an event that happens like clockwork every 27.1 years and results in the star fading in brightness by one-half. Professional and amateur astronomers around the globe are watching, and the International Year of Astronomy 2009 marked the eclipse as a flagship "citizen science" event. More information is at http://www.citizensky.org .

Astronomers study these eclipsing binary events to learn more about the evolution of stars. Because one star passes in front of another, additional information can be gleaned about the nature of the stars. In the case of Epsilon Aurigae, what could have been a simple calculation has instead left astronomers endlessly scratching their heads. Certain aspects of the event, for example the duration of the eclipse, and the presence of "wiggles" in the brightness of the system during the eclipse, have not fit nicely into models. Theories have been put forth to explain what's going on, some quite elaborate, but none with a perfect fit.

The main stumper is the nature of the naked-eye star -- the one that dims and brightens. Its spectral features indicate that it's a monstrous star, called an F supergiant, with 20 times the mass, and up to 300 times the diameter, of our sun. But, in order for this theory to be true, astronomers had to come up with elaborate scenarios to make sense of the eclipse observations. They said that the eclipsing, companion star must actually be two so-called B stars surrounded by an orbiting disk of dusty debris. And some scenarios were even more exotic, calling for black holes and massive planets.

A competing theory proposed that the bright star was actually a less massive, dying star. But this model had holes too. There was no simple solution.

Hoard became interested in the problem from a technological standpoint. He wanted to see if Spitzer, whose delicate infrared arrays are too sensitive to observe the bright star directly, could be coaxed to observe it using a clever trick. "We pointed the star at the corner of four of Spitzer's pixels, instead of directly at one, to effectively reduce its sensitivity." What's more, the observation used exposures lasting only one-hundredth of a second -- the fastest that images can be obtained by Spitzer.

The resulting information, in combination with past Spitzer observations, represents the most complete infrared data set for the star to date. They confirm the presence of the companion star's disk, without a doubt, and establish the particle sizes as being relatively large like gravel rather than like fine dust.

But Hoard and his colleagues were most excited about nailing down the radius of the disk to approximately four times the distance between Earth and the sun. This enabled the team to create a multi-wavelength model that explained all the features of the system. If they assumed the F star was actually a much less massive, dying star, and they also assumed that the eclipsing object was a single B star embedded in the dusty disk, everything snapped together.

"It was amazing how everything fell into place so neatly," said Steve Howell of the National Optical Astronomy Observatory in Tucson, Ariz. "All the features of this system are interlinked, so if you tinker with one, you have to change another. It's been hard to get everything to fall together perfectly until now."

According to the astronomers, there are still many more details to figure out. The ongoing observations of the current eclipse should provide the final clues needed to put this mystery of the night sky to rest.

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

whitney.clavin@jpl.nasa.gov

ssc2010-01

jpl2010-002