Whilst best known for its surveys of the stars and mapping the Milky Way in three dimensions, ESA's Gaia has many more strings to its bow. Among them, its contribution to our understanding of the asteroids that litter the Solar System. Now, for the first time, Gaia is not only providing information crucial to understanding known asteroids, it has also started to look for new ones, previously unknown to astronomers.

Credit: Observatoire de Haute-Provence & IMCCE

Since it began scientific operations in 2014, Gaia has played an important role in understanding Solar System objects. This was never the main goal of Gaia – which is mapping about a billion stars, roughly 1% of the stellar population of our Galaxy – but it is a valuable side effect of its work. Gaia's observations of known asteroids have already provided data used to characterise the orbits and physical properties of these rocky bodies more precisely than ever before.

"All of the asteroids we studied up until now were already known to the astronomy community,"

explains Paolo Tanga, Planetary Scientist at Observatoire de la Côte

d'Azur, France, responsible for the processing of Solar System

observations.

These asteroids were identified as spots in the Gaia data that were

present in one image and gone in one taken a short time later,

suggesting they were in fact objects moving against the more distant

stars.

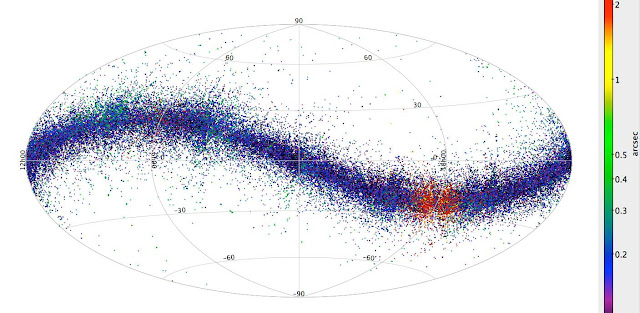

Gaia's asteroid detections

Credit: ESA/Gaia/DPAC/CU4, L. Galluccio, F. Mignard,

P. Tanga (Observatoire de la Côte d'Azur)

Once identified, moving objects found in the Gaia data are matched

against known asteroid orbits to tell us which asteroid we are looking

at. "Now," continues Tanga, "for the first time, we are finding moving

objects that can't be matched to any catalogued star or asteroid."

The process of identifying asteroids in the Gaia data begins with a

piece of code known as the Initial Data Processing (IDT) software –

which was largely developed at the University of Barcelona and runs at

the Data Processing Centre at the European Space Astronomy Centre

(ESAC), ESA's establishment in Spain.

This software compares multiple measurements taken of the same area and

singles out objects that are observed but cannot be found in previous

observations of the area. These are likely not to be stars but, instead,

Solar System objects moving across Gaia's field of view. Once found,

the outliers are processed by a software pipeline at the Centre National

d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES) data centre in Toulouse, France, which is

dedicated to Solar System objects. Here, the source is cross matched

with all known minor bodies in the Solar System and if no match is

found, then the source is either an entirely new asteroid, or one that

has only been glimpsed before and has never had its orbit accurately

characterised.

Although tests have shown Gaia is very good at identifying asteroids,

there have so far been significant barriers to discovering new ones.

There are areas of the sky so crowded that it makes the IDT's job of

matching observations of the same star very difficult. When it fails to

do so, large numbers of mismatches end up in the Solar System objects

pipeline, contaminating the data with false asteroids and making it very

difficult to discover new ones.

"At the beginning, we were disappointed when we saw how cluttered the

data were with mismatches," explains Benoit Carry, Observatoire de la

Côte d'Azur, France, who is in charge of selecting Gaia alert

candidates. "But we have come up with ways to filter out these

mismatches and they are working! Gaia has now found an asteroid barely

observed before."

Asteroid Gaia-606 on 26 October 2016.

Credit: Observatoire de

Haute-Provence & IMCCE

The asteroid in question, nicknamed Gaia-606, was found in October 2016

when Gaia data showed a faint, moving source. Astronomers immediately

got to work and were able to predict the new asteroid's position as seen

from the ground over a period of a few days. Then, at the Observatoire

de Haute Provence (southern France), William Thuillot and his colleagues

Vincent Robert and Nicolas Thouvenin (Observatoire de Paris/IMCCE) were

able to point a telescope at the positions predicted and show this was

indeed an asteroid that did not match the orbit of any previously

catalogued Solar System object.

However, despite not being present in any catalogue, a more detailed

mapping of the new orbit has shown that some sparse observations of the

object do already exist. This is not uncommon with new discoveries

where, as with Gaia-606 (now renamed 2016 UV56), objects that first

appear entirely new transpire to be re-sightings of objects whose

previous observations were not sufficient to map their orbits.

"This really was an asteroid not present in any catalogue, and that is

an exciting find!" explains Thuillot. "So whilst we can't claim this is

the first true asteroid discovery from Gaia, it is clearly very close

and shows how near we are to finding a never-before-seen Solar System

object with Gaia."

Asteroid search region

Credit: ESA

Gaia is an ESA mission to survey one

billion stars in our Galaxy and local galactic neighbourhood in order to

build the most precise 3D map of the Milky Way and answer questions

about its origin and evolution.

The mission's primary scientific product will be a catalogue with the

positions, motions, brightnesses, and colours of the more than a

billion surveyed stars. The first intermediate catalogue was released in

September 2016. In the meantime, Gaia's observing strategy, with

repeated scans of the entire sky, is allowing the discovery and

measurement of many transient events across the sky: among these are the

detection of candidate asteroids which are subsequently observed by

astronomers in the Gaia Follow-Up-Network. During the five-year nominal

mission, Gaia is expected to observe about 350 000 asteroids of which a

few thousand will be previously unknown.

About Gaia

Gaia is an ESA mission to survey one

billion stars in our Galaxy and local galactic neighbourhood in order to

build the most precise 3D map of the Milky Way and answer questions

about its origin and evolution.

The mission's primary scientific product will be a catalogue with the

positions, motions, brightnesses, and colours of the more than a

billion surveyed stars. The first intermediate catalogue was released in

September 2016. In the meantime, Gaia's observing strategy, with

repeated scans of the entire sky, is allowing the discovery and

measurement of many transient events across the sky: among these are the

detection of candidate asteroids which are subsequently observed by

astronomers in the Gaia Follow-Up-Network. During the five-year nominal

mission, Gaia is expected to observe about 350 000 asteroids of which a

few thousand will be previously unknown.

Credit: Google Earth

The nature of the Gaia mission leads to

the acquisition of an enormous quantity of complex, extremely precise

data, and the data-processing challenge is a huge task in terms of

expertise, effort and dedicated computing power. A large pan-European

team of expert scientists and software developers, the Data Processing

and Analysis Consortium (DPAC), located in and funded by many ESA member

states, and with contributions from ESA, is responsible for the

processing and validation of Gaia's data, with the final objective of

producing the Gaia Catalogue. Scientific exploitation of the data only

takes place once the data are openly released to the community.

Contacts

Paolo Tanga

Observatoire de la Côte d'Azur, France

Email: Paolo.Tang@aoca.eu

Benoit Carry

Observatoire de la Côte d'Azur, France

Email: benoit.carry@oca.eu

William Thuillot

Observatoire de Paris, France

Email: William.Thuillot@obspm.fr

Timo Prusti

Gaia Project Scientist

Directorate of Science

European Space Agency

Email: timo.prusti@esa.int

Source: ESA/Gaia